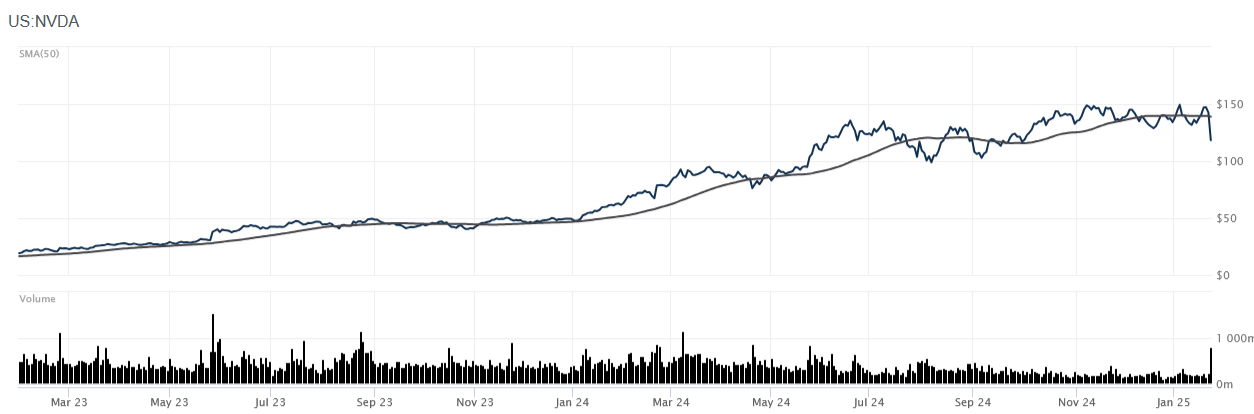

At time of writing, the Nasdaq—the primary US-market index that tracks the tech sector—suffered a 3% drop attributable to Nvidia’s share price and lost a historic $600B in value in a single day of trading. This came on the news of China’s DeepSeek, a ChatGPT rival, that functions at an order of magnitude lower cost in both energy and chip usage.

Nvidia’s rapid growth in profits and, in turn, value as a stock have been driven by chip demand for processor-hungry LLMs. Obviously, news that suggests a different, more efficient approach is bad news for Nvidia and its heavy investment in that market.

Naturally, we all hate AI slop because we have mostly functional forebrains that haven’t been melted into butter by watching people cut soap on TikTok or whatever. Because of that, there’s been a lot of (wild, incorrect) speculation that Nvidia and other major players in the tech space that have invested and perhaps overinvested in highly speculative “AI” tech will suddenly implode because their stock price fell sharply and might have further to fall yet in the near future.

I won’t single out one person’s dumb post to mock them, so here’s a stock image of a dog.

This is a mistake for several reasons.

One is that well-established tech companies like Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, and Google (Alphabet, if you’re nasty) and their stock prices are riding ten-year highs. Moreover, it’s a very common opinion these stocks are significantly overvalued in a broadly overheated equity market and a correction of some kind is coming. While that correction might hit hard, it’s unlikely to wipe out well-established firms for another reason.

Unlike a lot of newer tech companies that have never posted a profit, the long-standing market moves like Nvidia et al. have strong records of profits and, more important, considerable reserves of cash on hand.

For these and many other reasons, these long-standing companies will not collapse entirely any time soon. Critically, stock valuation and company valuation are not the same. A well-established company with substantial assets and a significant volume of available cash does not collapse because its stock value drops for a while. A few days of relatively normal bad news can’t do that. The story is probably different for smaller, newer, more speculative firms offering services based on a completely imaginary market, but we’re not talking about them because I’m not Ed Zitron.

Anyway, let’s talk about the word “cash” in this context, because it’s interesting if you’re a nerd and might even be useful in your life.

Exciting.

There’s a term in finance we’re referencing when we say “cash” in this context.

Cash on hand.

Normal people would probably consider “cash” actual, factual money. Actual dollar bills in your possession or in a bank account. In everyday, colloquial English, when we talk about how much cash someone has, we’re asking if they opened up all their bank accounts and added the balances together, how much cash do they have?

Even in that context, it’s not exactly accurate. It’s less accurate still when we’re talking about an institution because cash on hand includes cash and also cash equivalents.

In short, a cash equivalent is anything that can be immediately and reliably converted into cash.

When you read a balance sheet and there’s a line that says “cash on hand”, it’s adding literal money in bank accounts with assets that can be reliably converted into more liquid cash on very short notice. In this case, “short notice” is within 90 days because a multi-trillion-dollar corporation can’t break its leg and have a bill it unexpectedly needs to pay next month.

Something important to note here is the word “reliably” I used in the last paragraph. This is why stock, for instance, is not a cash equivalent despite being a liquid asset. You can’t always sell a large volume of stock when you want and its value is highly volatile. Meanwhile, a short-term government bond is a cash-equivalent because it can be sold within 90 days, its value is incredibly reliable, and it is guaranteed* to sell.

*-”Guaranteed” is another word we need to define here because it’s guaranteed by an institution and in the sense society and the entire economy won’t collapse in the next 90 days and while that feels more likely now than it did maybe a year ago, on the extreme off-hand chance it does, a company’s cash-on-hand won’t exactly be relevant if we’re hunting dogs for food because it’s Mad Max times plus at that point even money in the bank won’t matter because they’ve been converted into fortresses by local warlords and also money will have no value, so we can say it’s guaranteed.

To make this hopefully even easier to understand, let’s talk about how you might manage your money assuming you have enough money to start making decisions with it.

If you’ve ever worked in finance, I’m sorry, it’s time to talk about the buckets.

Northwestern uses a pyramid, but I personally hate the pyramid.

Close your eyes and imagine a better world. You’re bringing in $250,000 a year, your kids are bizarrely affordable, you paid off your car, and you own your own home with a low-interest mortgage. You’re reliably bringing more money than you spend and you need a savings and investment strategy. Very cool.

Every financial advisor will give you some shade of the following advice: You need to split up your money. Some money for right now to pay for bills, just goofing around, and unforeseen immediate expenses. Other money you’re socking away for a long-term purpose like buying a Lexus in five years. Even more, different, other money you’re using to make money. Then, of course, you have that last pile of money for retirement because in this beautiful Elysium of a mind palace, that’s something you get plan for.

They will show you a Powerpoint slide that looks basically exactly like this.

Stolen shamelessly from Premier Investments & Wealth Management, with whom I do not have nor have ever had any affiliation. Like the text at the bottom says, none of this is financial advice, but if it was, it would be good financial advice. Which it’s not.

For the purposes of this spiel, the first bucket is the one we care about.

Think about how you would save money in this scenario. You want enough money to guarantee that if something unexpectedly bad—or good but expensive—happens that insurance won’t instantly cover, you’re not out of money and won’t need to dip into your investment fund at an inconvenient time in the market, pull out of your retirement, or borrow against your life insurance.

That last one is something people with actual money get to do, and it’s extremely cool.

This presents a problem, though. Banks kind of suck.

Interest rates are never as high as inflation, which means if you put money in a bank account and let it sit there, you’re not losing money, but that money is losing value. This doesn’t matter if you have to nervously check your savings account and do some head math before you go to Taco Bell, but if you already have a few months worth of savings in the bank, it’s actually a big problem.

Importantly, what you don’t want to do is put that extra short-term savings in the stock market because equity is volatile. What if your idiot child slams your 2017 Lincoln Navigator through the wall of the high school girls lacrosse team’s equipment barn, you might need a lot of money right now, and what if the market’s down? You’d selling your savings at a loss!

Luckily, there are other classes of assets.

A good example is a municipal bond fund which is exactly as exciting and volatile and its deeply boring name implies, which is to say “not very”. This is a fund of different bonds issued by municipalities. They produce more revenue than a bank account, sometimes nearly as much as the inflation rate and rarely slightly more, and they’re incredibly stable both in the revenue they generate and overall value.

If you want your money to grow over the long-term, you don’t put it in one of these funds, but if you think you might need extra money immediately at some point, they’re an option because you can sell your position in them and turn it back into cash within two or three days. Most importantly, if a municipal bond fund’s value collapses it means multiple American cities have gone bankrupt and, at that point, you’re probably not too worried about cash anyway because something has gone catastrophically wrong.

This means an investment in a fund like this, even if it’s not “guaranteed” (we talked about that earlier) is incredibly liquid and reliable in its value, that makes it a cash equivalent.

If you have $50,000 in the bank and another $200,000 in things like a municipal bond fund, that means you have $250,000 in cash and cash equivalents. If for some reason you need more money and it’s a problem insurance can’t cover, ideally, you’re still working and bringing in revenue, and in however long it takes you to burn through $150,000, more of your money will be in a position you convert it cash. Maybe the stock market improves, maybe some bonds you’re holding come to term, whatever it is, you can use that immediate cash on hand—which isn’t just cash money—to get you to that future date.

Finally, we’re back to talking about Nvidia because this is one way in which the economics of a household and the economics of a multi-trillion-dollar corporation work similarly.

Neither you nor Nvidia would meaningfully benefit from having multiple years worth of savings sitting in a bank account. Maybe more important, that much money making so little interest when it could be doing literally anything more productive is irresponsible because, again, that money would be losing value over time. Instead, both you and Nvidia need enough operating capital (you know, money) to get by if something bad happened and reach a future date when even more money could be pulled out of less liquid assets to turn into more operating capital.

That’s why cash on hand is a useful number. It’s an expression of several things, but maybe most of all, is how stable an entity—whether a household or a company—is and how certain it is to be able to pay its bills if something bad happens.

This was a long road to hoe, I realize, with a maybe unnecessary detour into personal finance, but it’s an issue I’ve seen a lot of people be completely wrong about, even angrily so. There are many metrics to determine the health and stability of a company, but if you think it’s at risk of suddenly collapsing, look at its cash on hand.

Just like a family, if there’s a lot of cash on hand, it’s almost certainly not at risk of collapse.

P.S. Once again none of this was financial advice and if you show this post to a financial advisor, I will hunt you down like an animal.